The Discarded Archive

|

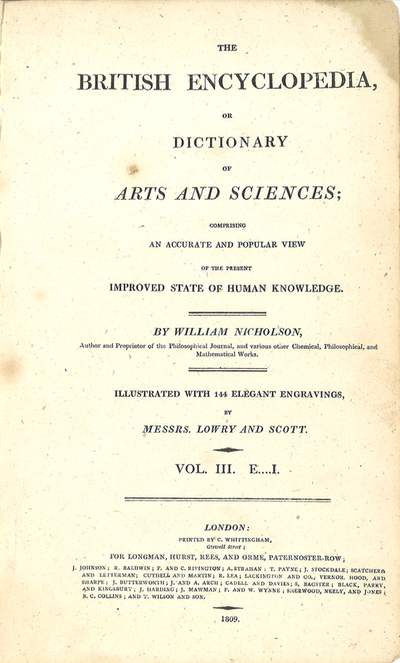

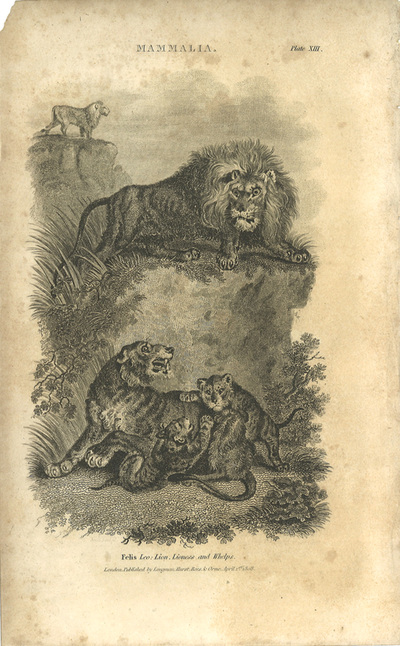

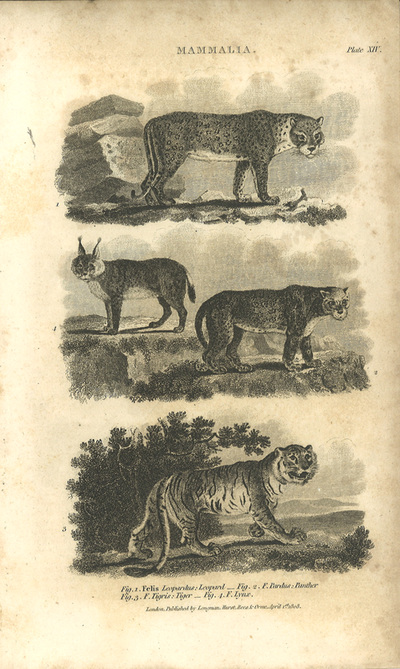

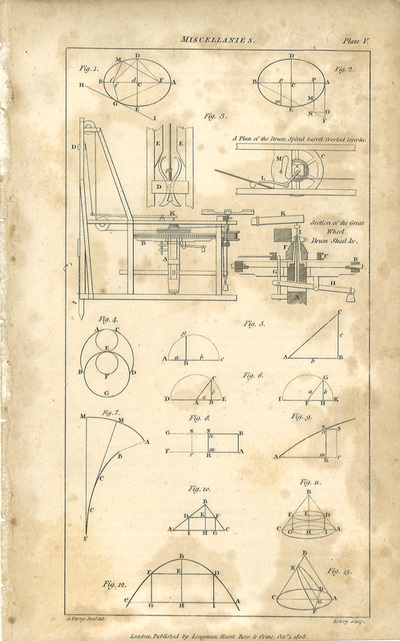

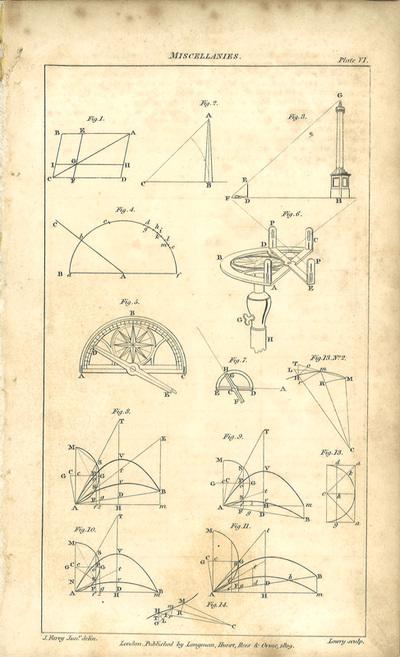

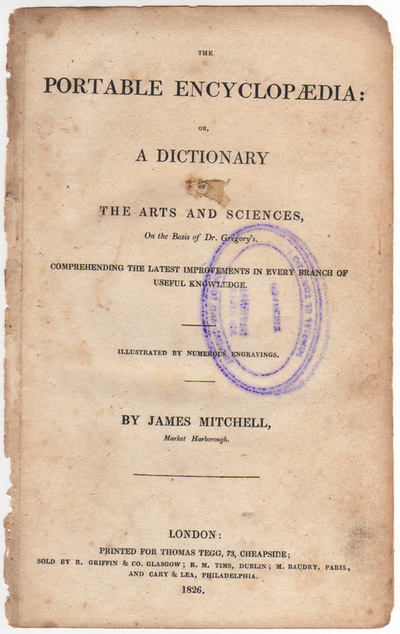

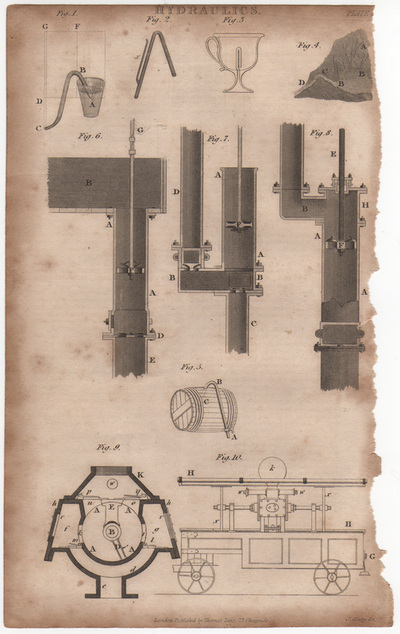

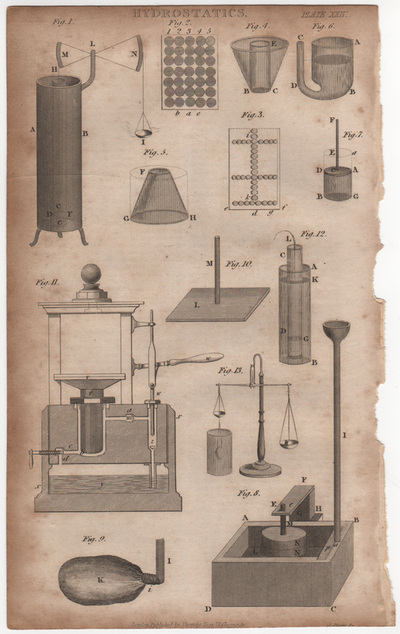

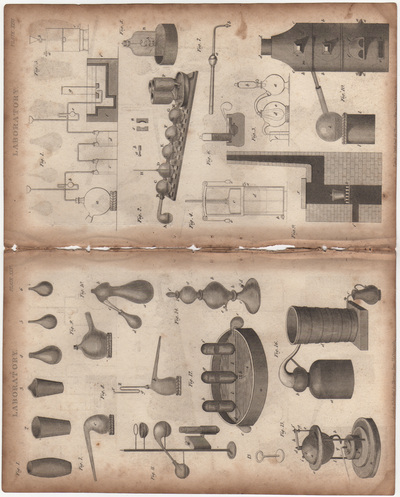

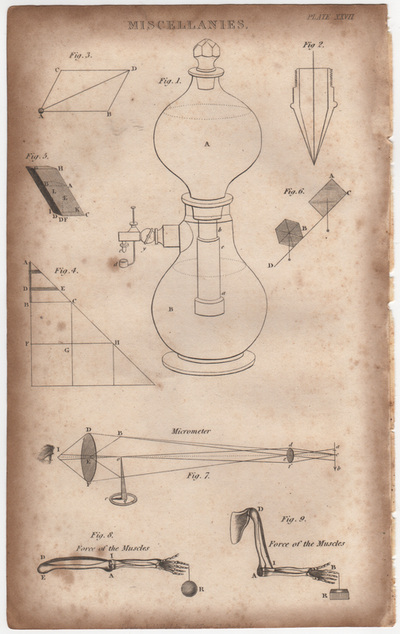

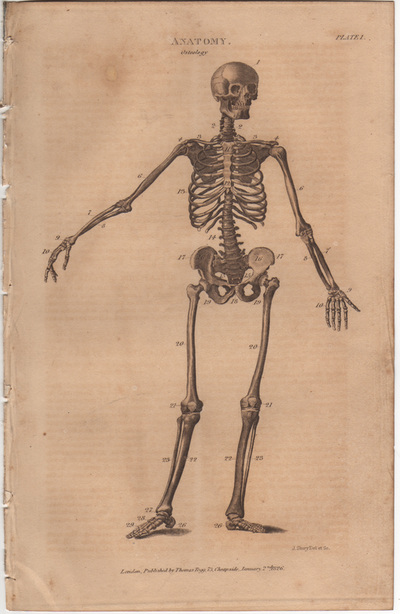

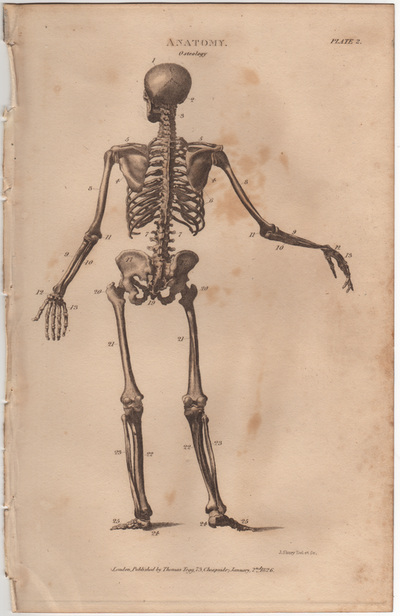

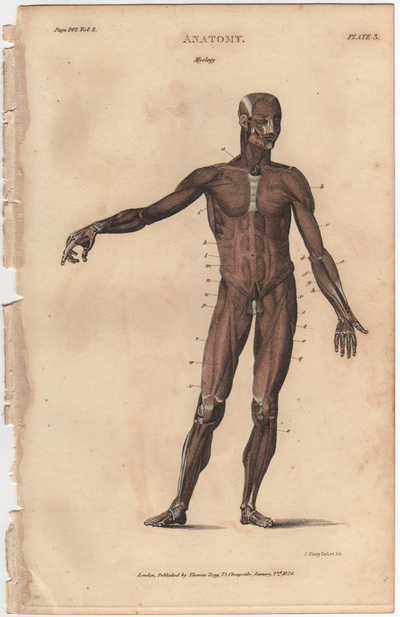

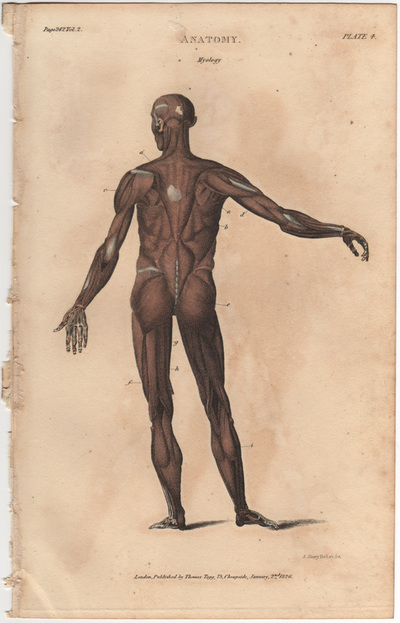

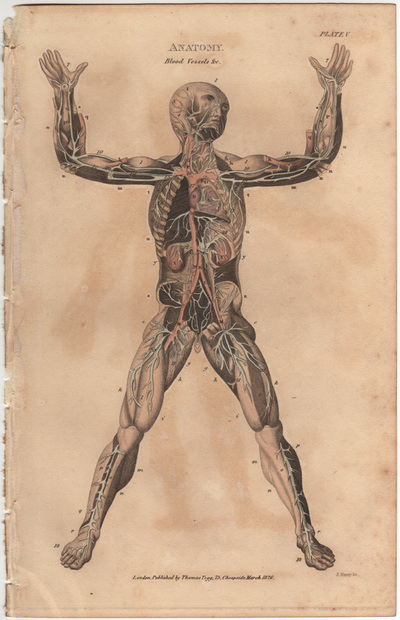

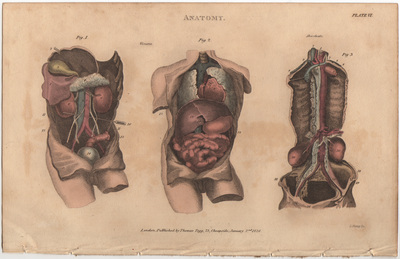

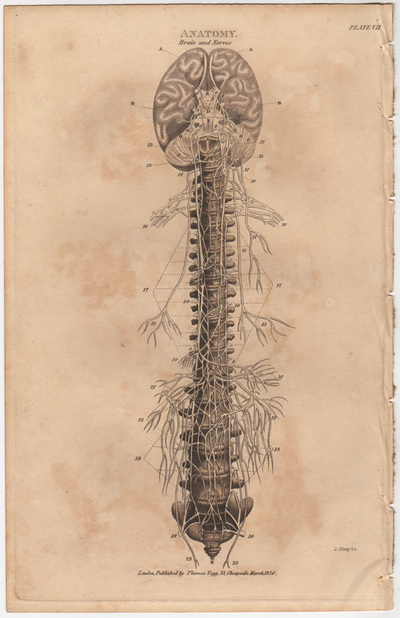

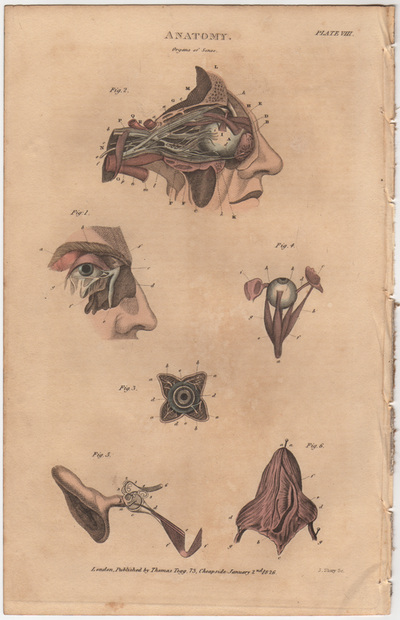

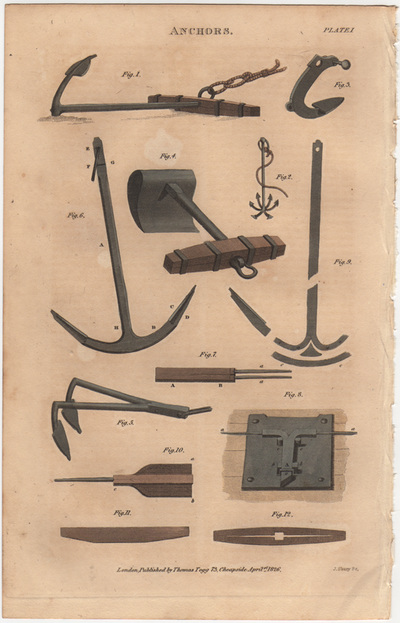

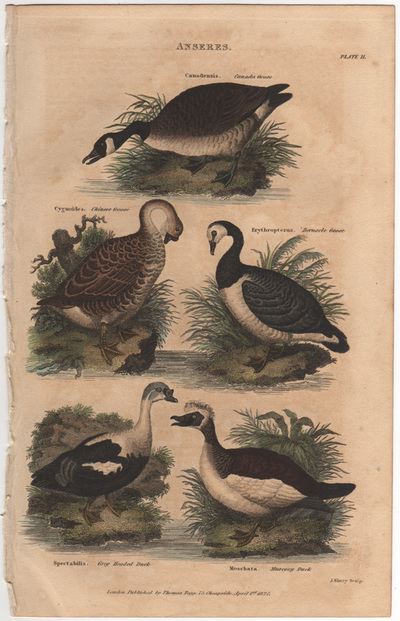

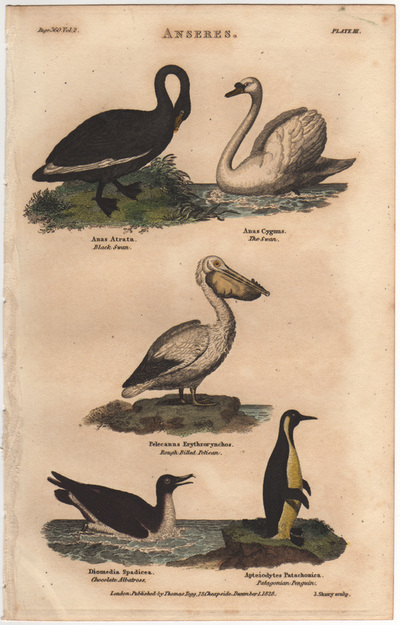

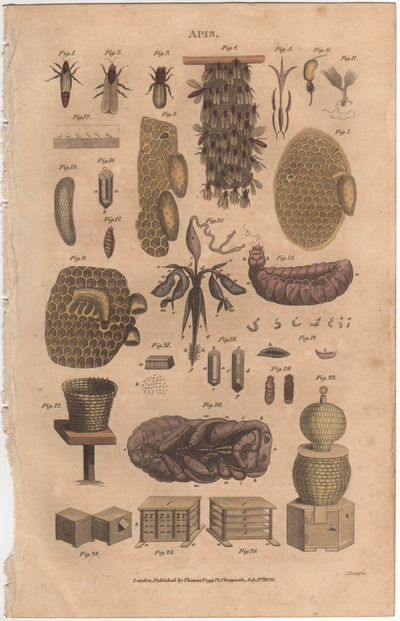

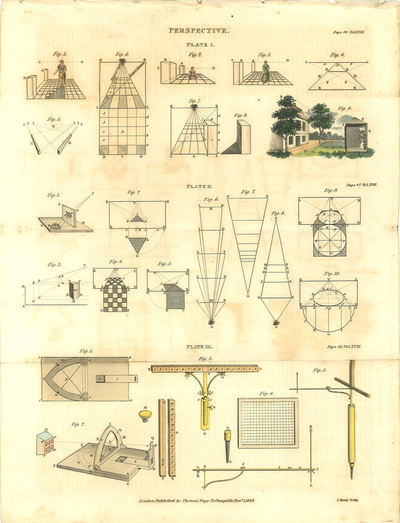

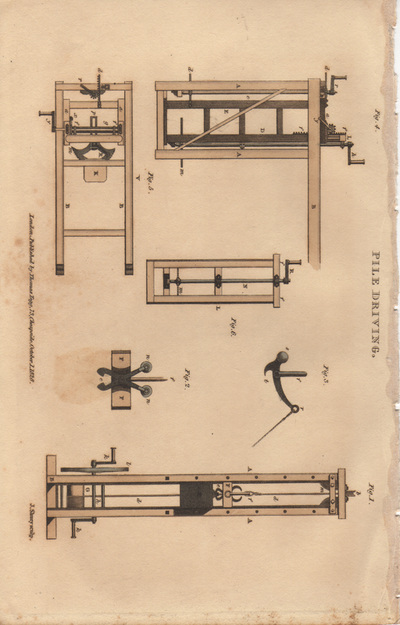

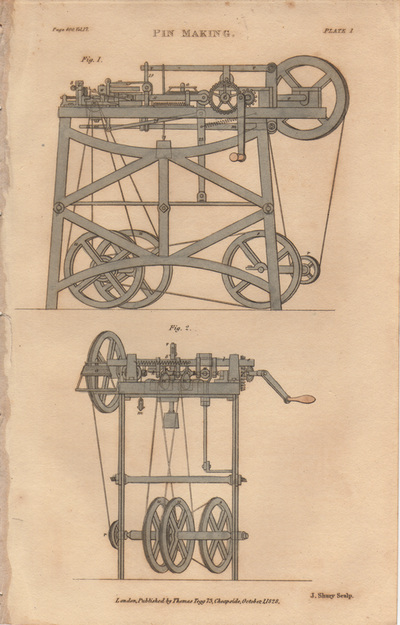

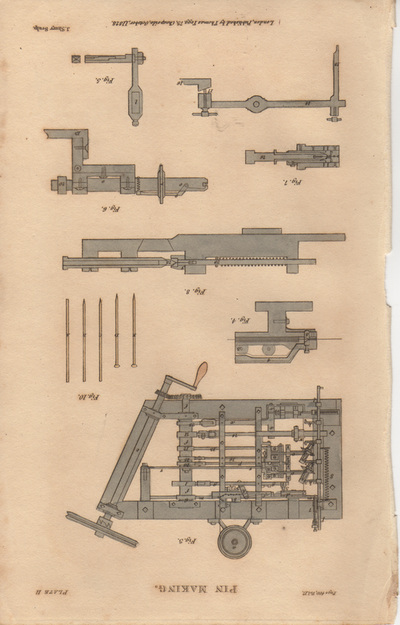

The Discarded Archive is a collection comprised mainly of 18th, 19th, and early 20th Century reference documents that were being discarded by the National Archives of Trinidad and Tobago. Showing signs of irreparable damage, most of them were considered no longer viable as complete texts. And, given their condition, it seemed unlikely even a collector or skilled conservationist would have been able to fully restore them. Their disposal was inevitable, as the task of preserving them falls outside the parameters of the National Archives mission, which involves:

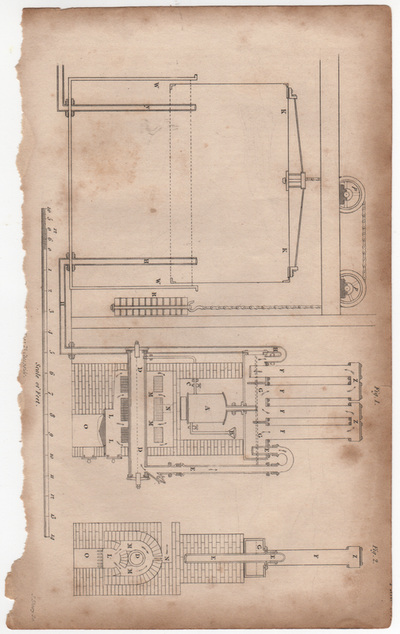

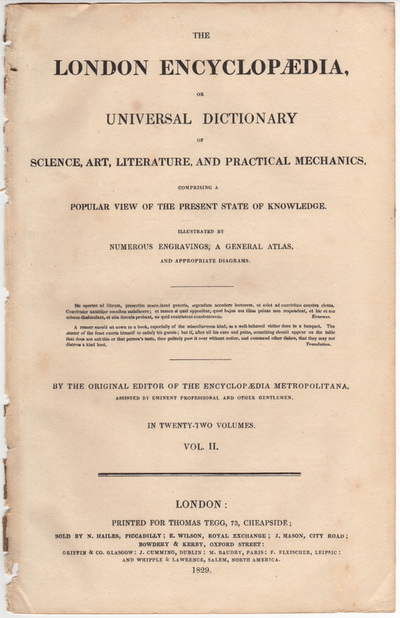

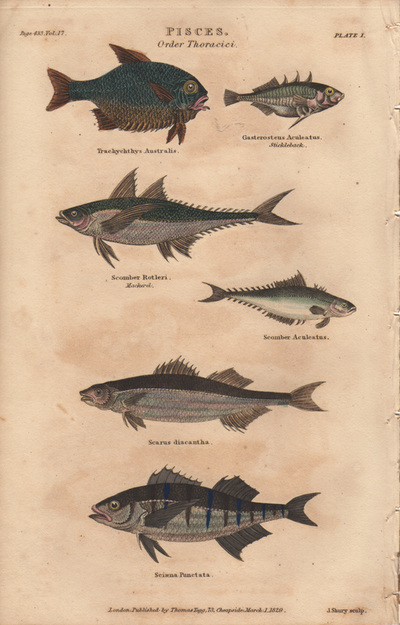

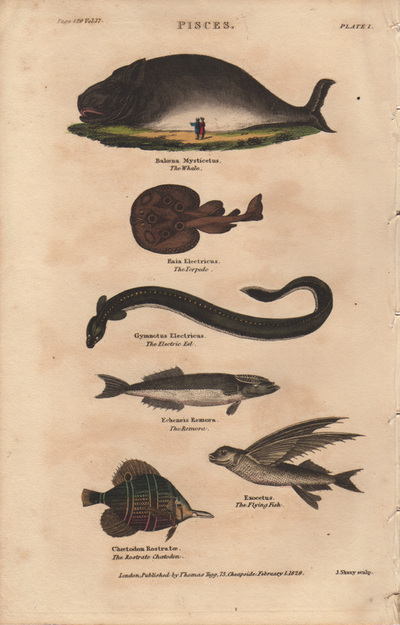

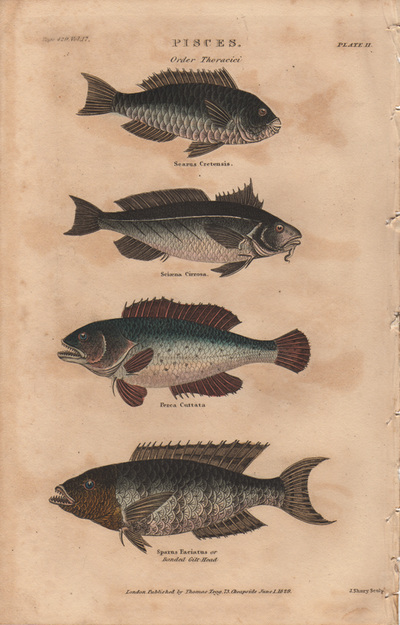

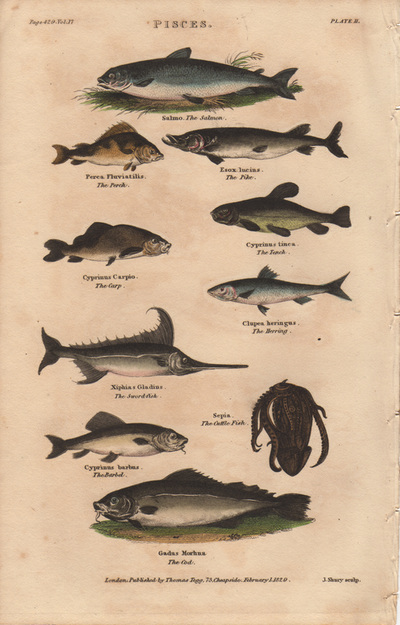

"[P]reserving and protecting Trinidad and Tobago’s memory and maintaining the democratic rights of citizens to have access to the records of the government. In order to fulfill our mandate we acquire, process, manage, and make accessible to citizens and researchers quality records documenting the broad spectrum of activities undertaken throughout the history of Trinidad and Tobago." We decided to digitize them. It is still a work in progress, pending the collection of metadata and more extensive analysis, but preliminary digitization is complete (tiff and jpeg), as well as a rudimentary cataloging system (titles, authors, publisher, sellers, dates, plate numbers). The originals have been sealed and stored. |

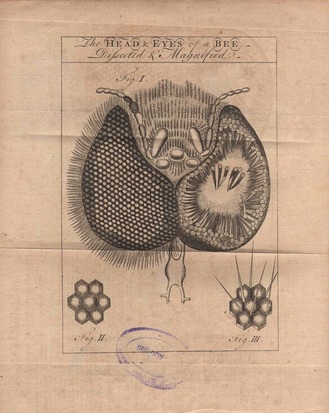

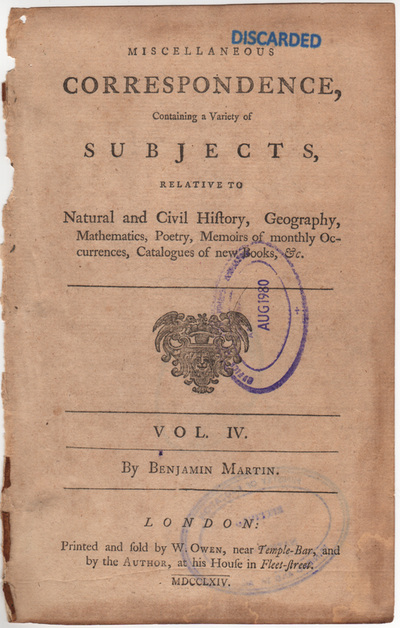

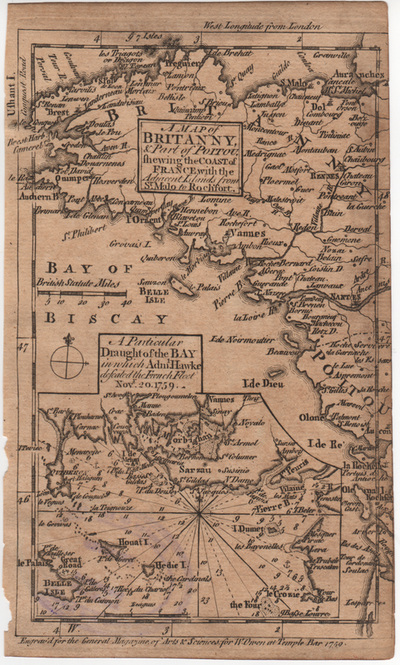

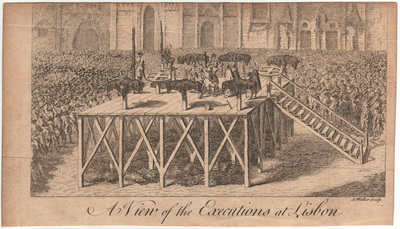

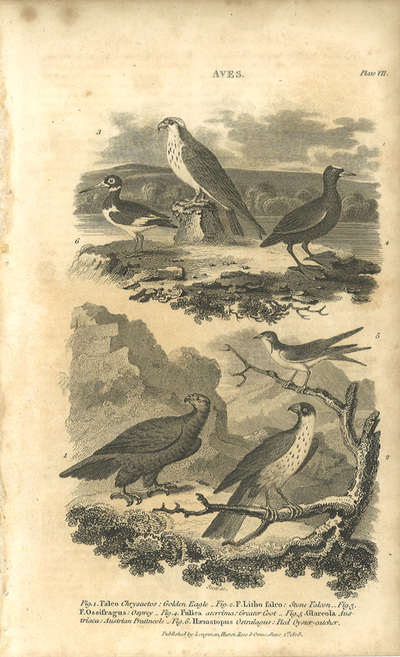

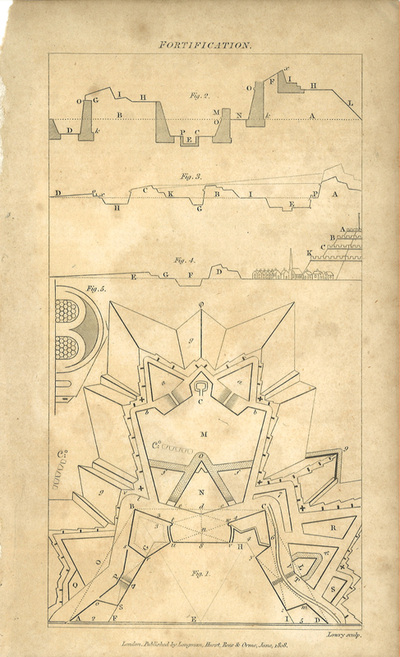

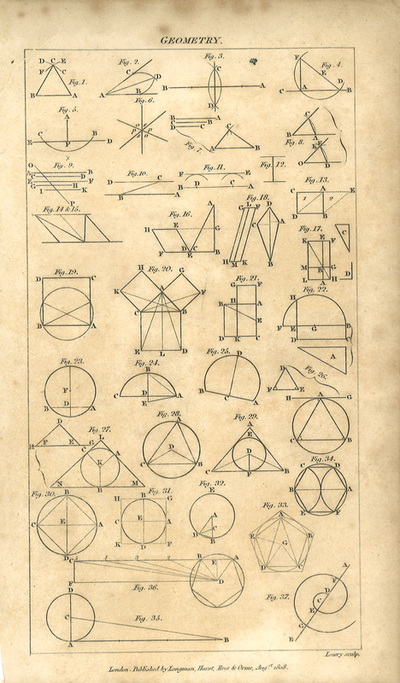

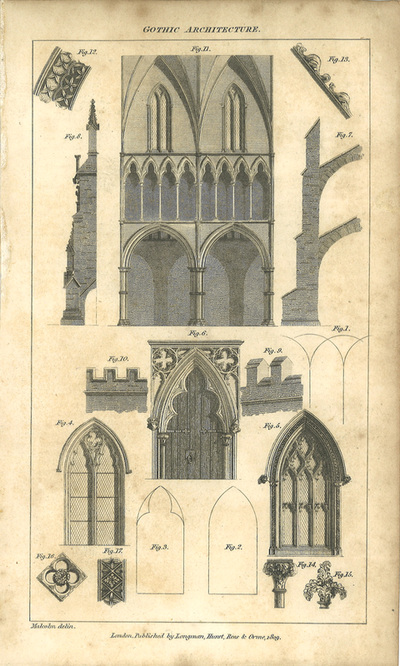

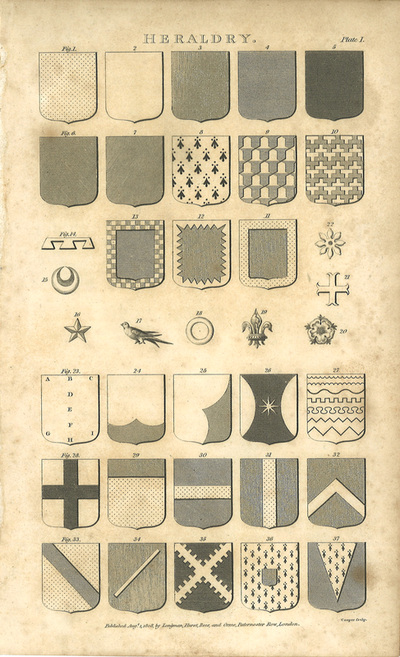

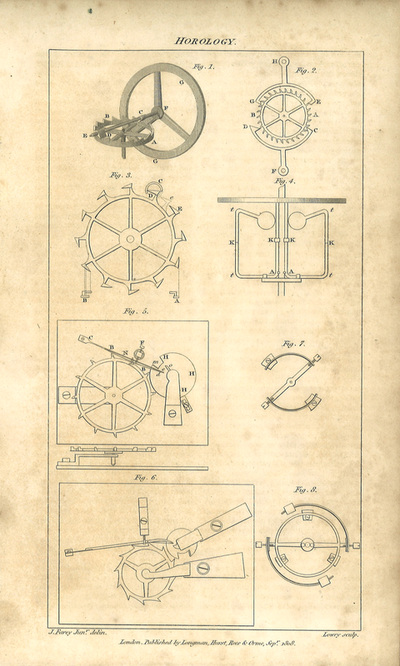

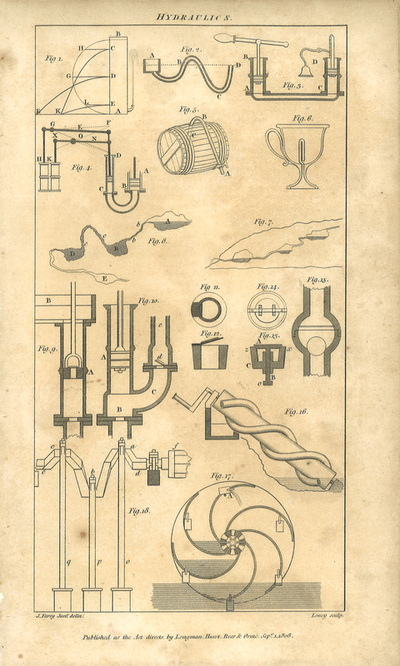

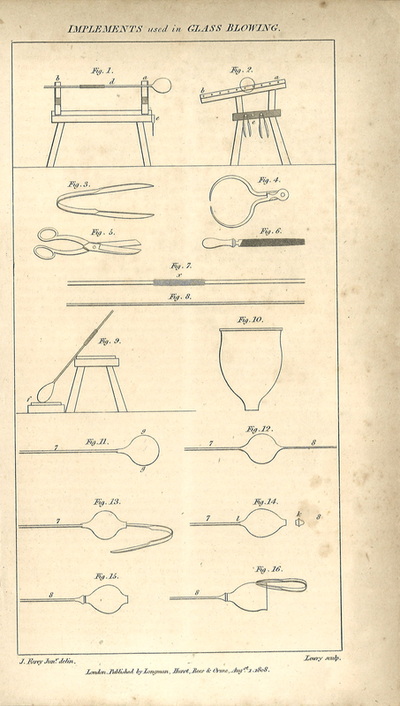

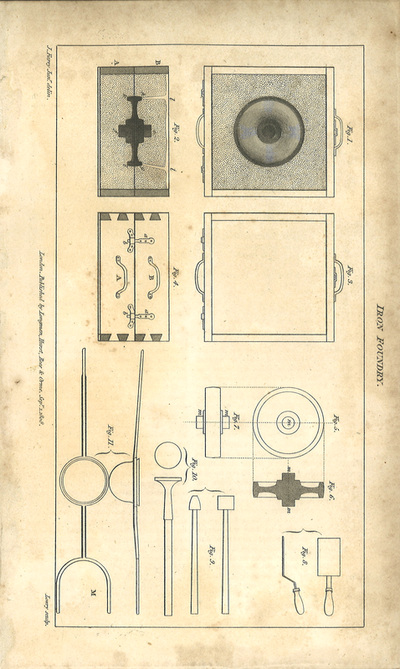

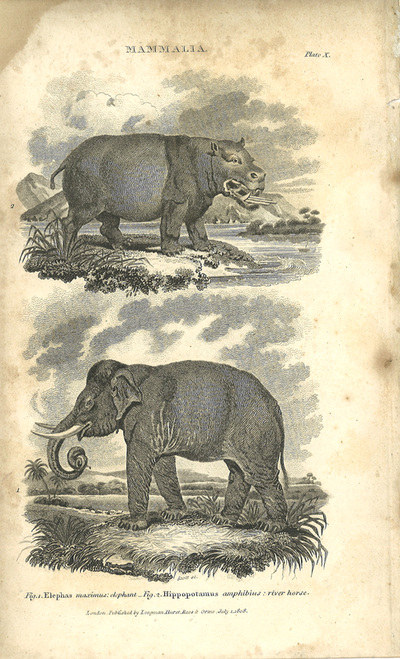

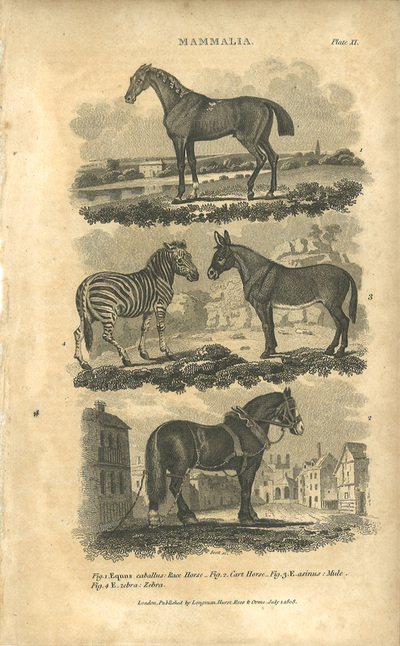

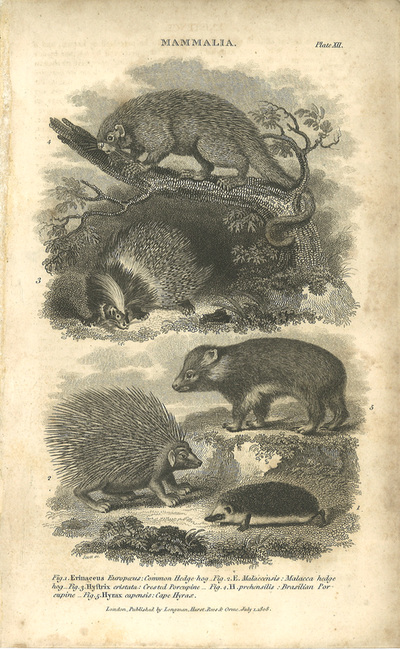

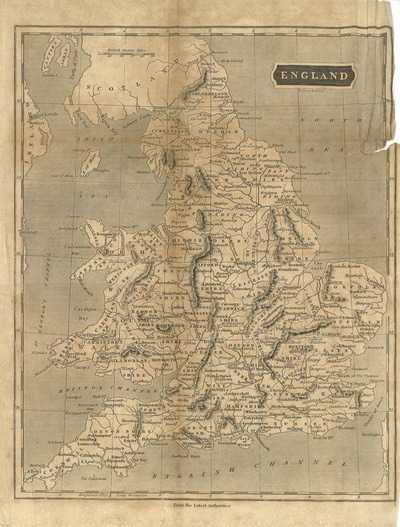

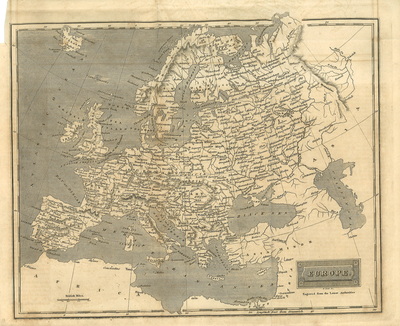

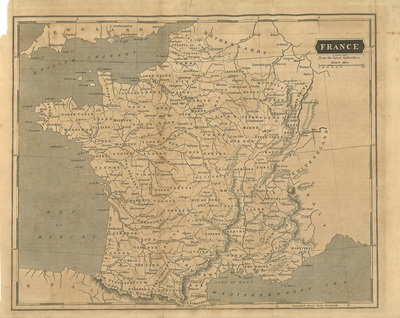

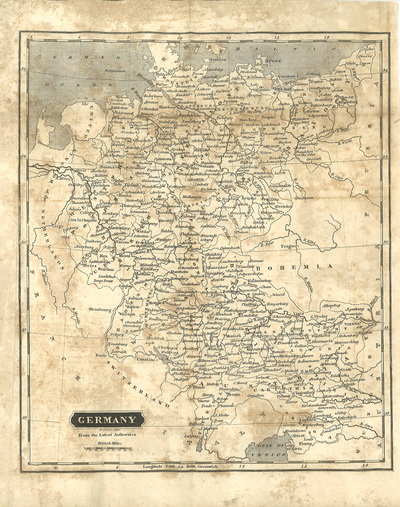

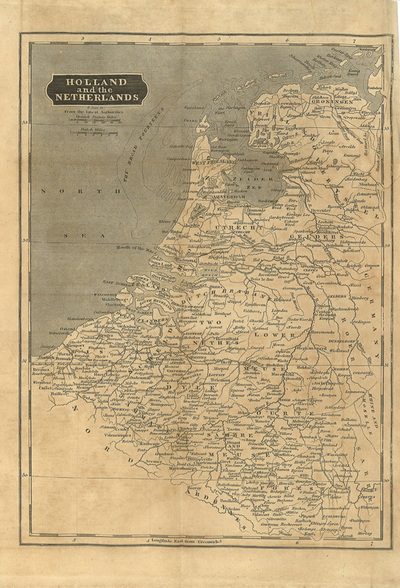

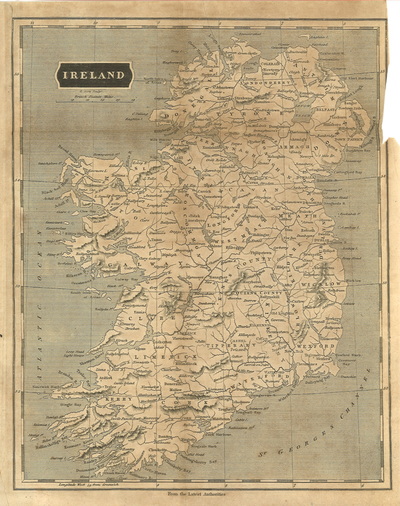

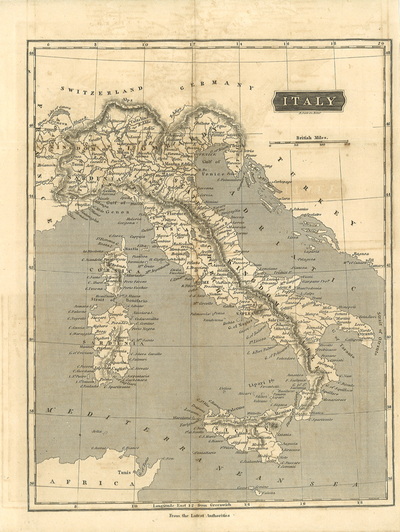

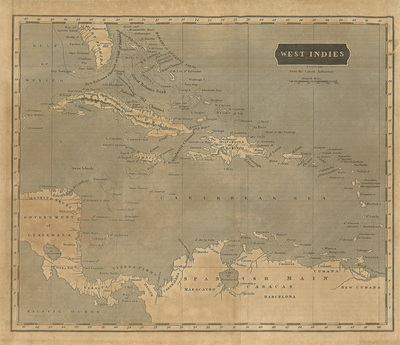

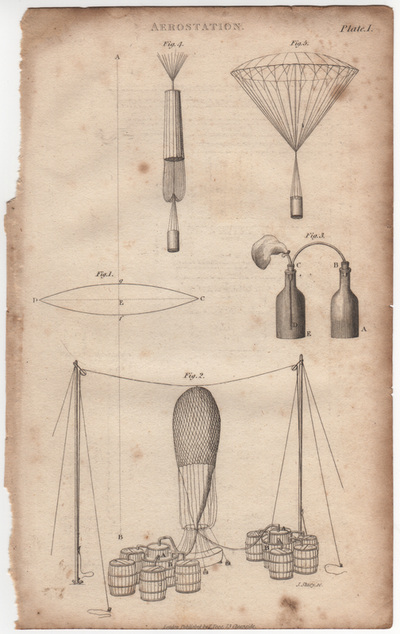

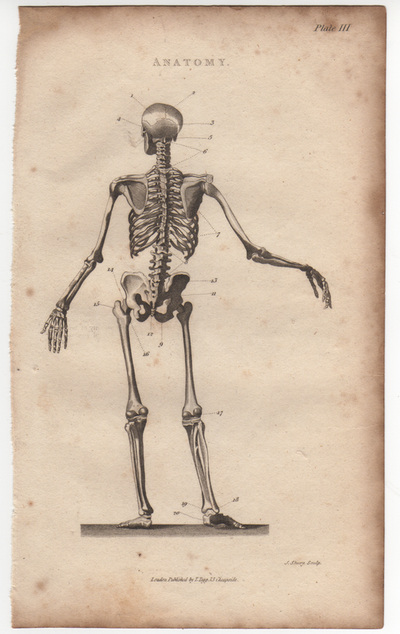

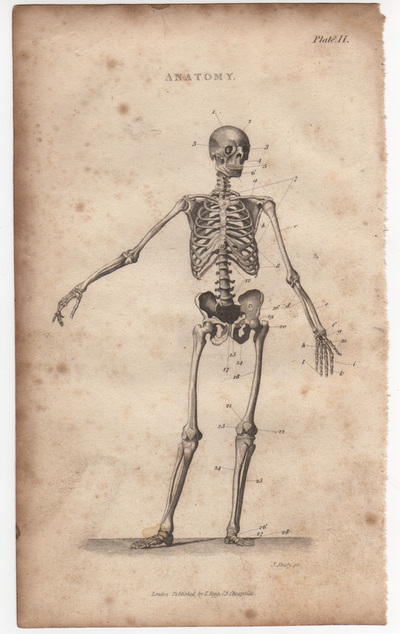

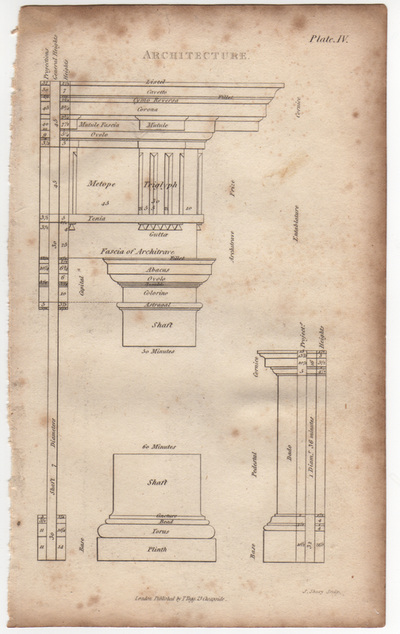

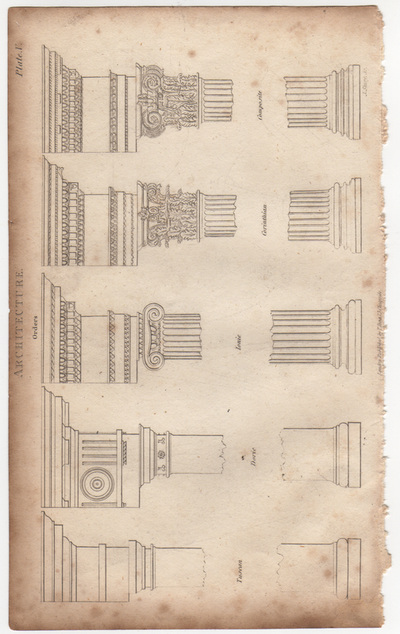

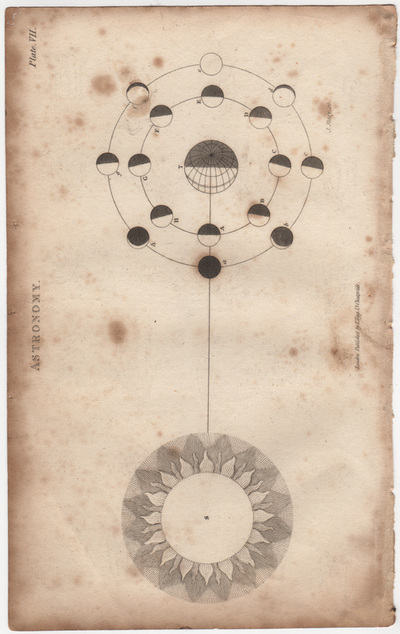

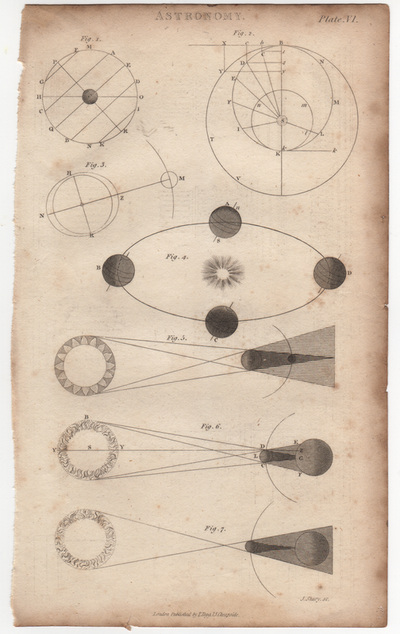

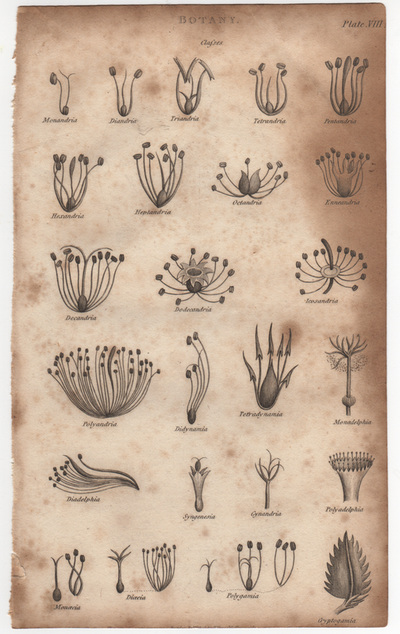

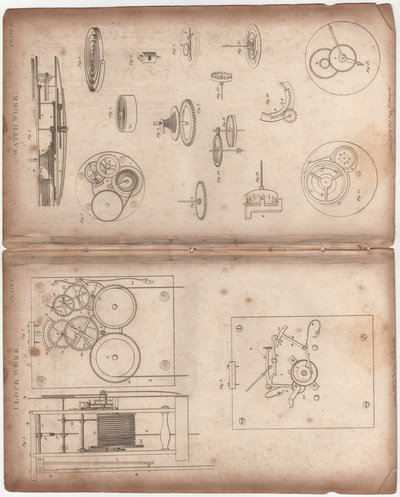

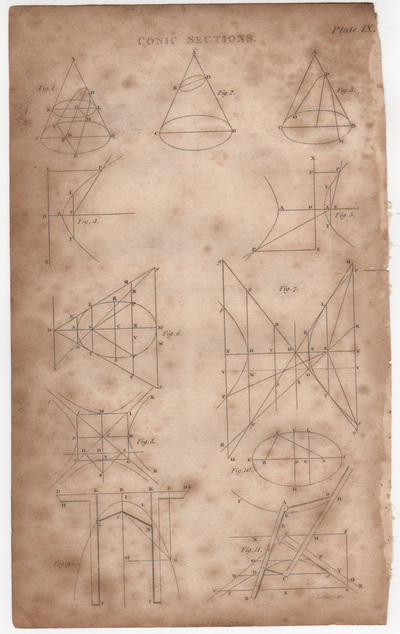

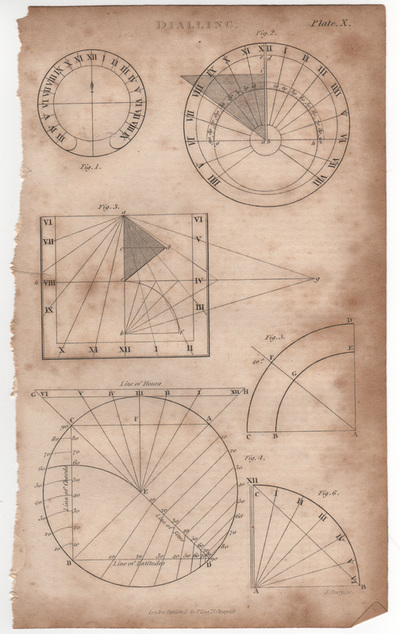

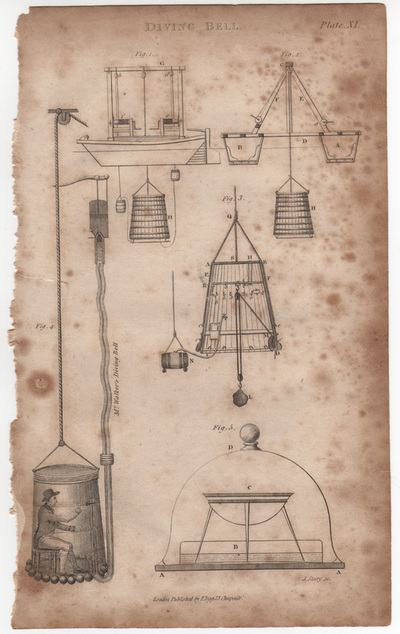

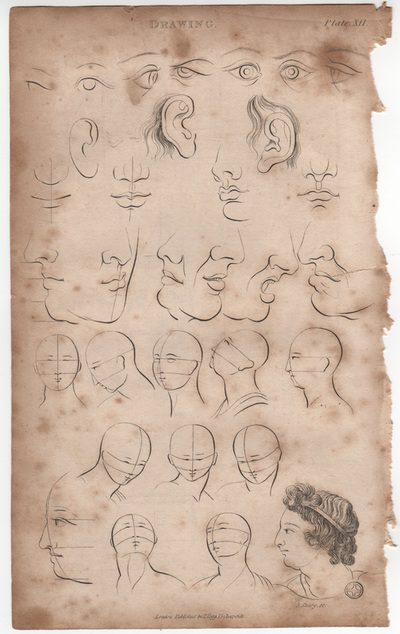

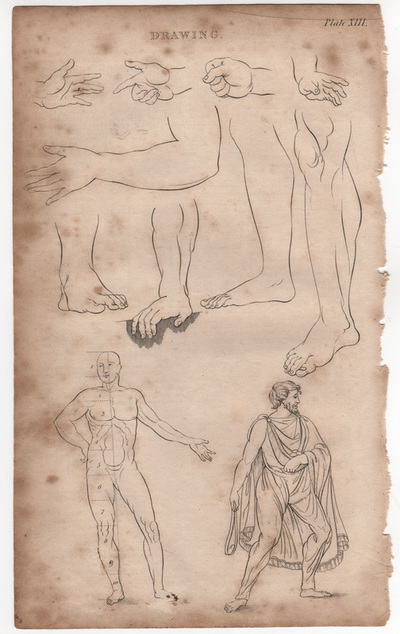

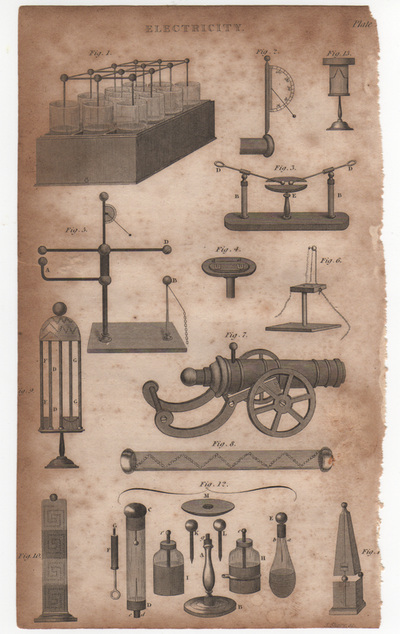

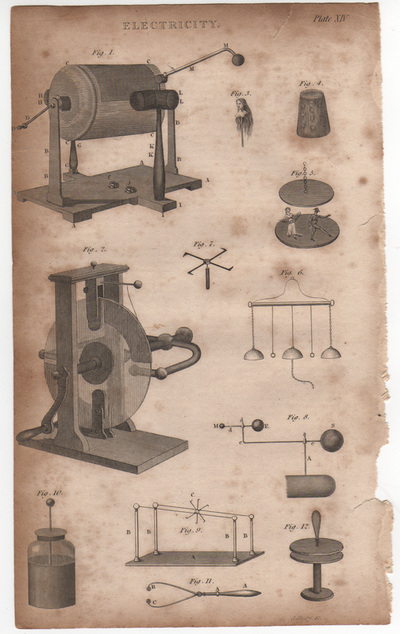

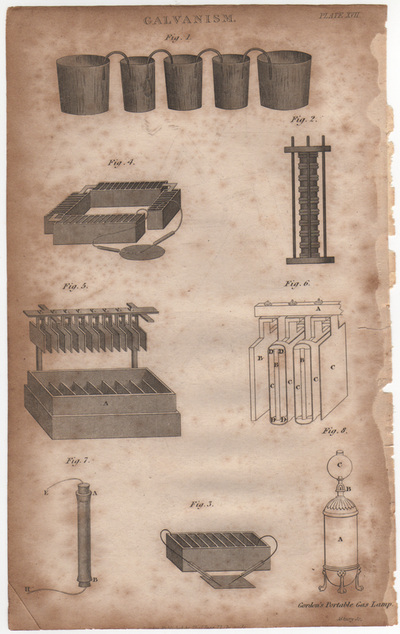

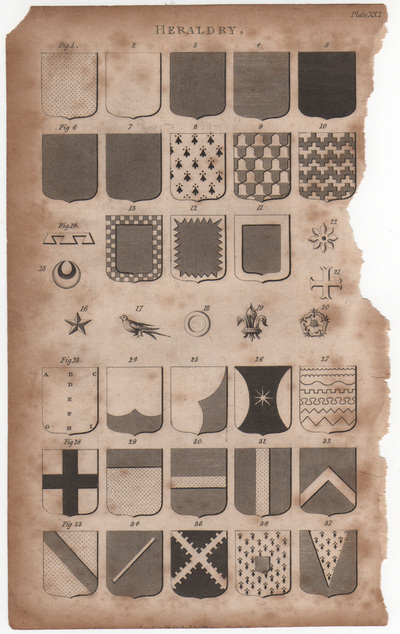

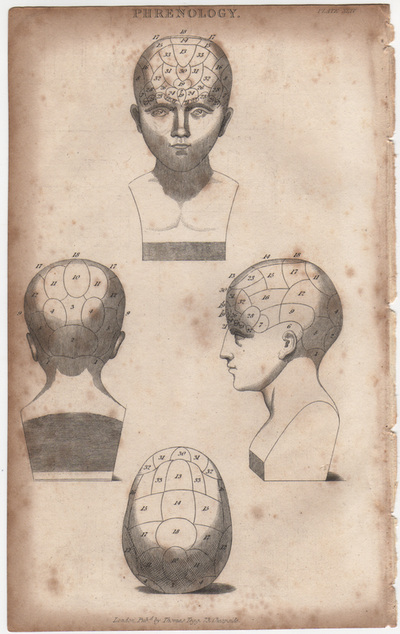

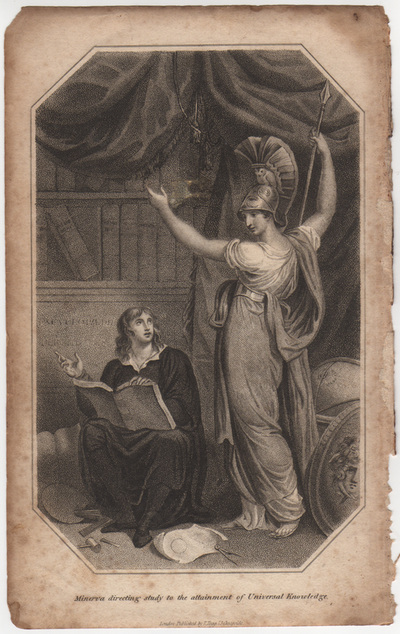

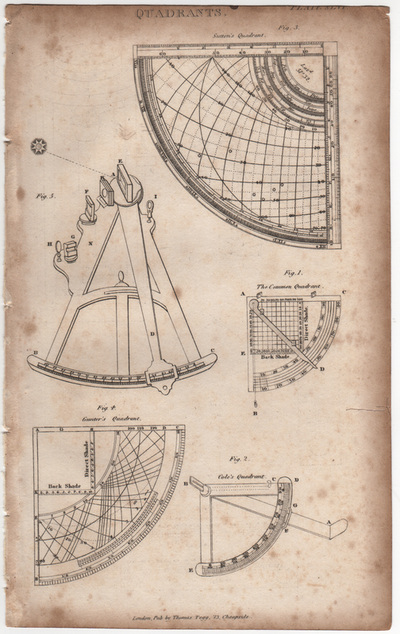

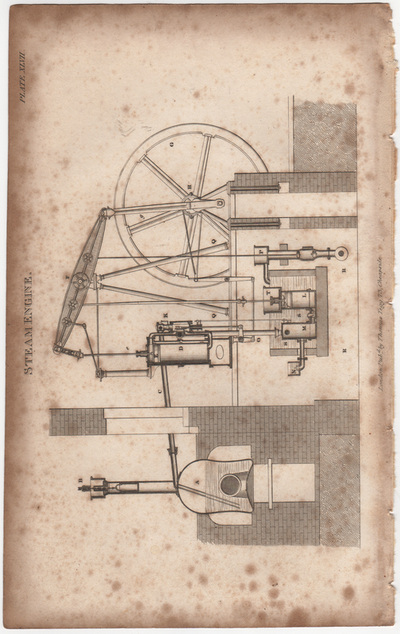

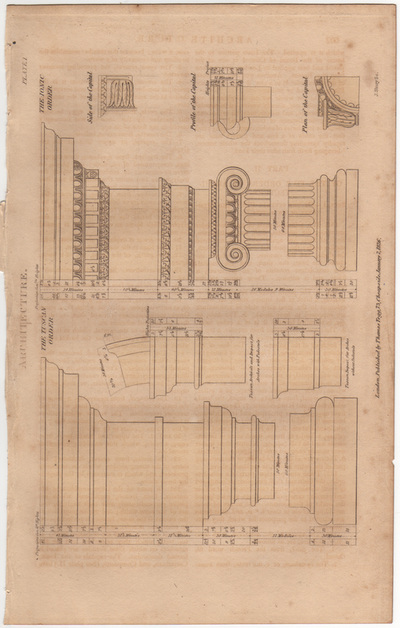

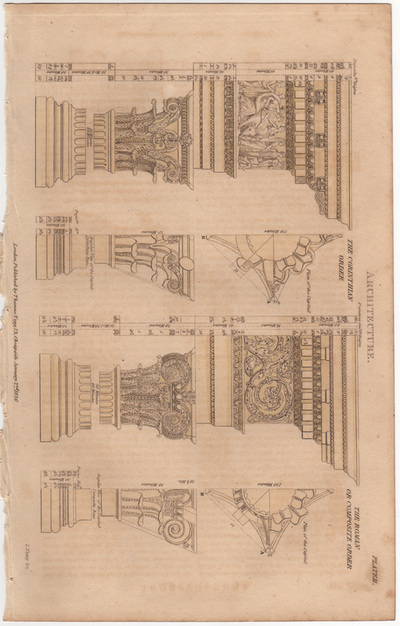

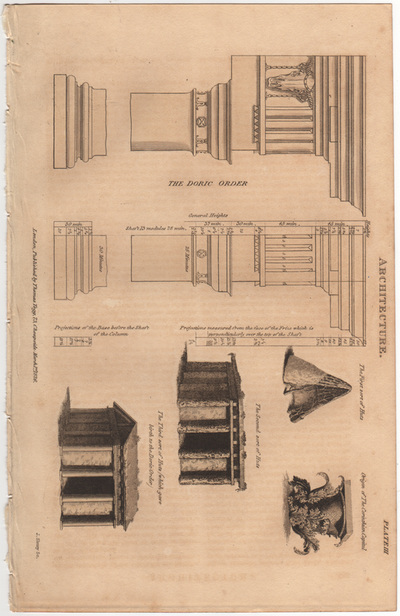

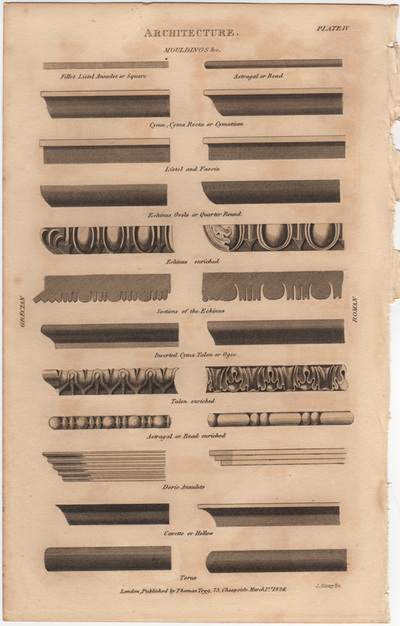

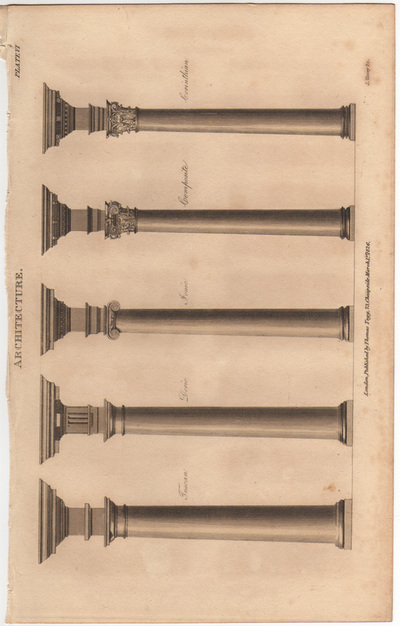

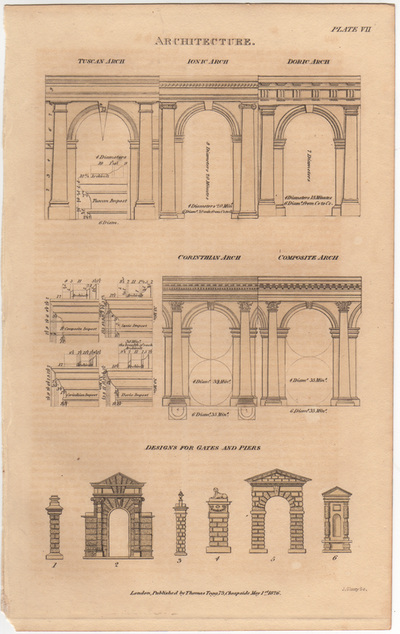

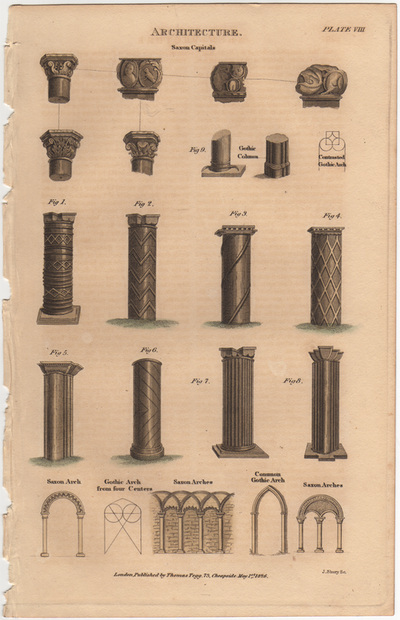

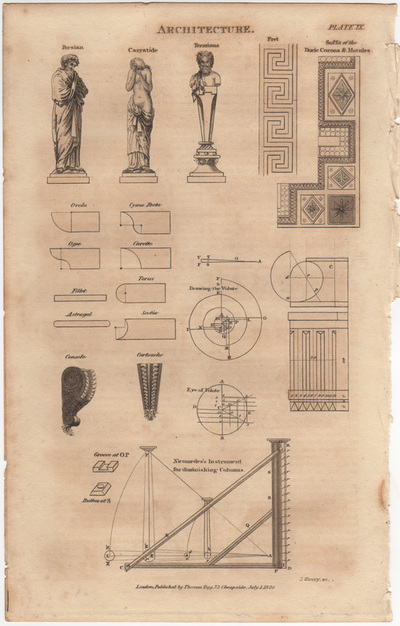

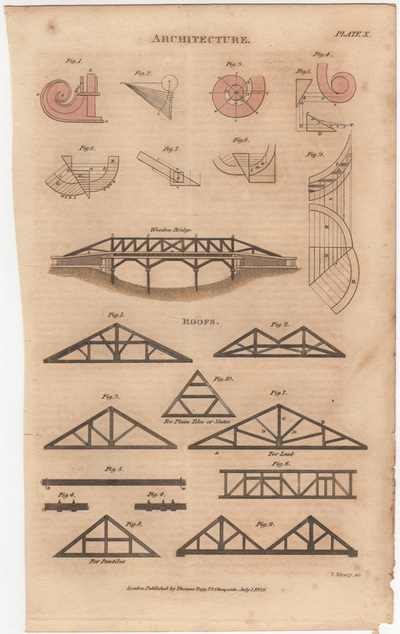

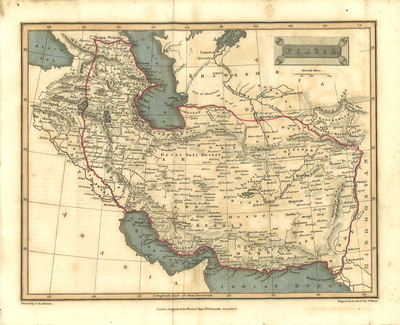

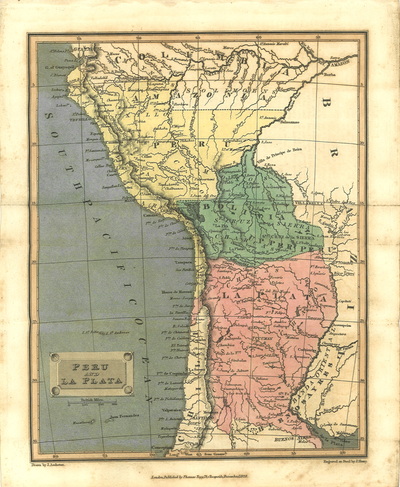

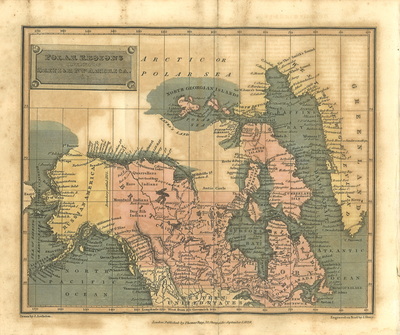

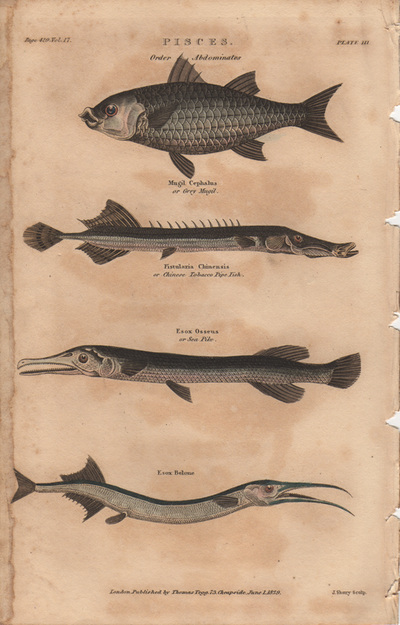

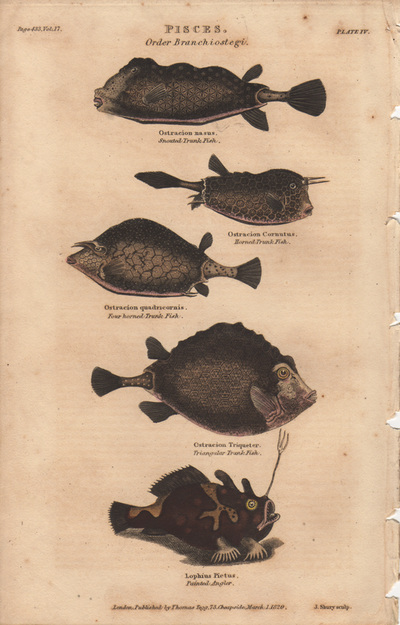

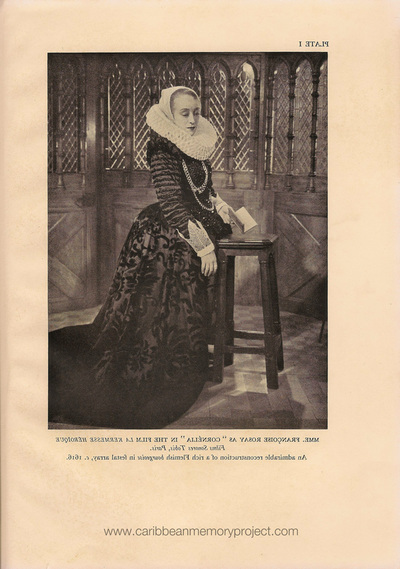

Prima facie, the documents are fairly unremarkable as historical artifacts, except perhaps to collectors. They were by no means ubiquitous in the Caribbean, but aside from their obvious age—the oldest, a few drawings from 1764—many households possessed a version of at least one of these encyclopedia. Most popular was the Encyclopedia Britannica—included in the main collection are some maps from Vol. 28, 1911. In these texts, many students at the upper-primary, secondary, and tertiary levels conducted research in a range of prescribed topics, for which the encyclopedia (as repositories of infinite knowledge) were perfectly equipped to serve as references for the shaping and reshaping of minds. Whatever we wanted to know could be found in those pages. Or so it seemed.

But where some see the unremarkable, others see the overarching imposition of hegemony. They see the normalization of learning imposed from above by the imperial state, or hegemon, and the subsequent acquiescence to that imposition as evidence of manipulation, marginalization, misrepresentation, and silencing on a deep cultural level. The convenience, of course, was by design. Clark and Ivanič put it rather succinctly when they note that, “such a perfectly ordered world [was] set up as an ideal by those who wish[ed] to impose their own social order upon society in the realm of language.” Language, as the vehicle for sanctioned knowledge. Needless to say, the inculcation of particular colonial values all but ensured the subjugation of other more indigenous and vernacular forms.

Put a slightly different way, the very unremarkability of these texts is not only evidence of a lasting colonial influence (that extends well into post-colonialism and successfully undermines the notion of sovereignty among post-independence states), but is evidence also of a rhetorical situation that provides practitioners with an opportunity to critically redress the operation of power on their ways of seeing and knowing—literally, these texts provide researchers with digital and material texts that can be reoriented toward the articulation of vernacular sensibilities. We are further reminded by Clark and Ivanič that,

But where some see the unremarkable, others see the overarching imposition of hegemony. They see the normalization of learning imposed from above by the imperial state, or hegemon, and the subsequent acquiescence to that imposition as evidence of manipulation, marginalization, misrepresentation, and silencing on a deep cultural level. The convenience, of course, was by design. Clark and Ivanič put it rather succinctly when they note that, “such a perfectly ordered world [was] set up as an ideal by those who wish[ed] to impose their own social order upon society in the realm of language.” Language, as the vehicle for sanctioned knowledge. Needless to say, the inculcation of particular colonial values all but ensured the subjugation of other more indigenous and vernacular forms.

Put a slightly different way, the very unremarkability of these texts is not only evidence of a lasting colonial influence (that extends well into post-colonialism and successfully undermines the notion of sovereignty among post-independence states), but is evidence also of a rhetorical situation that provides practitioners with an opportunity to critically redress the operation of power on their ways of seeing and knowing—literally, these texts provide researchers with digital and material texts that can be reoriented toward the articulation of vernacular sensibilities. We are further reminded by Clark and Ivanič that,

"hegemony is unstable and there are opportunities for change—sometimes more, sometimes fewer, depending on conditions in the wider socio-economic context. This is why is it so important to fight for an educational and cultural climate that encourages challenge and change, real empowerment and emancipation."

The imperative is clear. And just as there are things that should be taken for granted in the course of any inquiry, there are things that require our attention because they remind us, and others, that we are aware of our particular ways of seeing. This is especially important when dealing with a social formation that has historically been subject to disregard in the areas of knowledge-making and complex expression. The logic of this inquiry may be outlined like this: if it is true (or, at least, reasonable to suggest) that few things reinscribe empire and the concomitant inferiority of its subjects more effectively than the ubiquity of texts that define what has traditionally counted as knowledge, then it is equally true (or reasonable to suggest) that the deliberate resistance to these traditional assumptions is an act that is both deeply subversive and highly political.

Now, does this ensure decolonization? No, but it does provide an alternative context in which to effectively nurture the possibility and increase the probability of decolonization occurring among members of this social formation. So while it is true that these texts are not inherently Caribbean, and that they do not deal directly with overtly Caribbean topics in the way other Caribbean archives do, this fact (coupled with their problematic unremarkability) affords opportunities for critical engagement from a slightly different perspective. Because these texts were literally owned by a post-independence Caribbean state institution—purchased, coded, cataloged, stored, discarded, and now digitized and repurposed—the archive has been subject to a series of deliberate moves to control the dissemination of its varied content. As readers, we will certainly recognize parallels, as we trace their transformation from the constraining materiality of embodied histories to the constitution of a digitized functionality.

Now, does this ensure decolonization? No, but it does provide an alternative context in which to effectively nurture the possibility and increase the probability of decolonization occurring among members of this social formation. So while it is true that these texts are not inherently Caribbean, and that they do not deal directly with overtly Caribbean topics in the way other Caribbean archives do, this fact (coupled with their problematic unremarkability) affords opportunities for critical engagement from a slightly different perspective. Because these texts were literally owned by a post-independence Caribbean state institution—purchased, coded, cataloged, stored, discarded, and now digitized and repurposed—the archive has been subject to a series of deliberate moves to control the dissemination of its varied content. As readers, we will certainly recognize parallels, as we trace their transformation from the constraining materiality of embodied histories to the constitution of a digitized functionality.

|

|

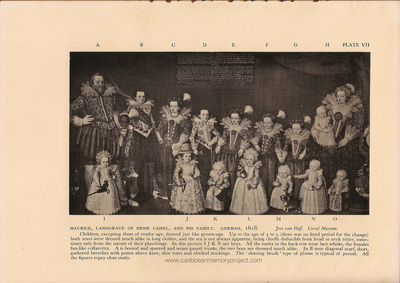

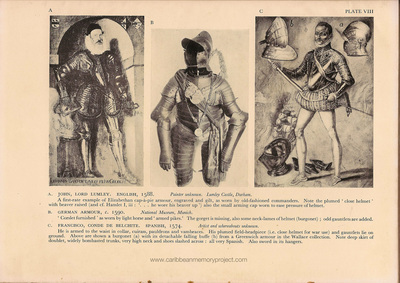

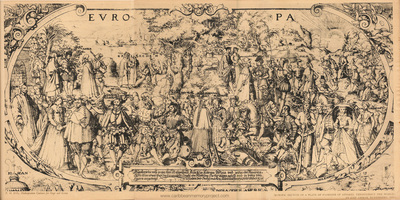

Additional volumes include:

The Century, Vol. 23, 1881-2. The Scruggs Maps, 1900. Chambers Encyclopaedia, 1908. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol. 28, 1911. The complete archive can be found at drbrowne.me/discarded-archive. |